DALLAS — In the wake of a favorable Internal Revenue Service ruling in December, the Texas Board of Education last week began the process of reopening and possibly doubling the bond-backing capacity of the Permanent School Fund.

The board on Friday discussed a new rule that allows the PSF to guarantee school bonds in an amount up to five times the fund’s $24 billion value. Until the IRS ruling, the fund could only back 2.5 times its value.

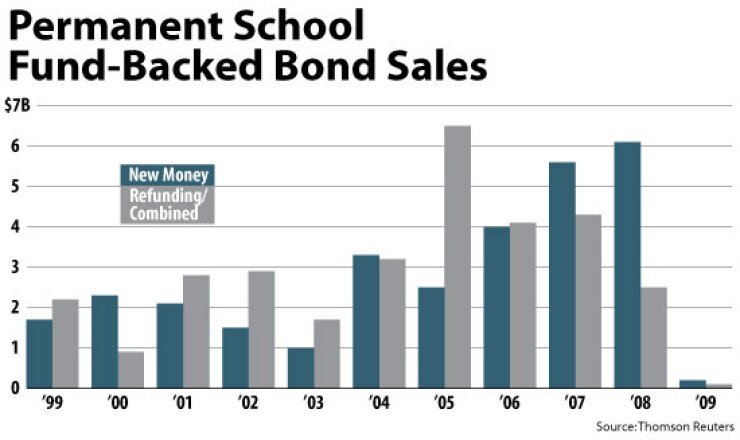

With the PSF’s value falling as low as $17 billion during the recession, the fund reached its capacity for providing bond guarantees in December 2008. That forced the Texas Education Agency to sideline the bond guarantee for all of 2009.

While school districts are eager to regain the PSF’s guarantee of triple-A ratings, the procedure for restarting the program is expected to take several months.

After Friday’s discussion, the Board of Education will consider amending its statement of investment objectives, policies, and guidelines at its March meeting, according to the board’s agenda.

A second reading and final adoption would then be presented at the May 2010 meeting with a proposed effective date of 20 days later. The rule change would require a two-thirds vote of the board.

Therefore, school districts would probably not have access to the PSF guarantee under the new capacity limits until June.

However, Adam Jones, deputy commissioner of finance and administration for the TEA, told the board that growth in the value of the fund through 2009 would probably allow some bond guarantees even under the old limits.

The higher capacity for the bond guarantee has been years in the making. The state Legislature approved the higher threshold in its 2007 session with further funding provisions in 2009.

During that time, the Board of Education had applied for IRS authorization to raise the capacity of the fund, approval that finally came last month.

While the TEA cannot yet act on applications, the agency began receiving them again in January after news of the IRS ruling was reported, said Lisa Dawn-Fisher, deputy associate commissioner for school finance.

The board stopped taking applications in December 2008 and formally froze the PSF program in March 2009. At that point, the TEA quit accepting applications altogether, even those that were contingent on reopening the PSF.

“We made a decision not to do that because when we closed it, we had no idea when we would reopen it,” Dawn-Fisher said.

While districts must submit new applications for the PSF guarantee, the fees submitted with the old applications will be applied, she said.

While the PSF was frozen, school districts had to decide whether to issue under their own underlying credit or wait for the return of the PSF. Districts with ratings of double-A-minus or better found they could still issue without excessively painful interest rate costs.

With the return of the PSF and the calming of the bond market, districts are expected to seek refundings for much-needed savings.

Adrian Galvan, managing director for financial adviser Estrada Hinojosa & Co., said he has already submitted applications for two clients seeking a refunding.

Under the proposed rule change for the PSF, the amount of time that districts are allowed for issuing bonds after receiving the guarantee would be doubled from the current three months to six months.

Dawn-Fisher said that some districts struggled to issue their bonds within the three month window.

Two districts that faced lawsuits over planned bond issues, the Houston Independent School District and the Waller Independent School District, barely made it to market in 2008 before the PSF guarantee expired.

One constraint on doubling the fund’s capacity to guarantee bonds would be the effect on the PSF’s ratings. The board would not raise the limit to the maximum allowed if it endangered the triple-A rating, according to Jones.

“That’s a discussion we will have with the rating agencies between now and May about how comfortable they are with the higher coverage,” he told the board.

While rating analysts have not yet assessed the impact of doubling the bond capacity, they have noted the scenario in recent affirmations of the triple-A ratings.

“Fitch views the potential increase as not threatening to credit quality because one of the conditions is that the increased leverage does not prevent the program from receiving a AAA rating,” Fitch Ratings analyst Andy Kaaz wrote. “The [Board of Education] intends to increase the fund’s capacity by only small increments.”

Another factor that could limit the PSF’s capacity is the rate of inflation, Jones noted. In its ruling, the IRS based its ratio on the actual dollar value of the fund as of Dec. 16, 2009.

“The IRS limit is fixed,” Jones said. “This has got to be good for seven or eight years, maybe more. But inflation will probably send bureaucrats back to the IRS sometime in the future.”

The PSF started as a $2 million legislative appropriation in 1854 to benefit the public schools of the state.

After the fund’s coffers were drained by railroad loan defaults and the Civil War, the Texas constitution of 1876 granted the fund certain state lands and all proceeds from the sale and resource income from these lands.

Over the years more public domain land and rights have been given to the fund.

In 1983, voters approved a constitutional amendment that allowed the PSF to guarantee public school district bonds. Since the passage of this amendment, $76.8 billion of such bonds have been guaranteed under the program. To qualify for PSF backing, districts have to pass academic and financial muster.

Since the Great Depression, no Texas school district has defaulted on a bond payment.

If one did so, the PSF would simply make the scheduled debt payment rather than assume the obligation for the entire debt, Jones said.

In the meantime, the fund would seek reimbursement of the bond payment from the district’s local tax base, he said.

In addition to backing bonds, the PSF is a major source of education revenue for school districts — in some places accounting for one-fourth of revenue for public education.

When investment results allow, funds are distributed to districts through a portion of the PSF known as the Available School Fund.

With the economic downturn since 2007, funds have not been available at times and have had to be made up by legislative appropriations.