WEST HAVEN, Conn. –- Fearing more draconian rule from Connecticut's oversight board for cities, West Haven officials expect to discuss revisions to the city's five-year financial plan on Monday night.

After years of budget deficits, the loss of manufacturing business and internal bickering, 55,000-population West Haven triggered the radar of the new

An estimated gap of $7.4 million exists for FY18, which began July 1, with no revenue enhancements in the budget.

"We have a terrible financial condition," first-year Mayor Nancy Rossi said at an Aug. 27 council meeting. She is reluctant to raise taxes, although her administration has cut expenses and implemented layoffs and furloughs.

Connecticut's General Assembly created the 11-member MARB when it passed its fiscal 2018 budget. The lone municipalities under its watch, West Haven and state capital Hartford, are in Tier III under a categorization system.

Tier III status enables MARB to approve city budgets, a five-year recovery plan, labor contracts and provide feedback on bond issuance. Tier IV, the strictest oversight, would expand the board's role, including tighter budgetary control and the ability to appoint a financial manager.

“We have to work with the MARB or we go to Tier IV,” Rossi said. “If we go into Tier IV, anything can happen. We would be far worse off.”

While its financial challenges generate fewer headlines within Connecticut than those of Hartford or neighboring New Haven, West Haven’s woes have prompted MARB to wield the Tier IV hammer.

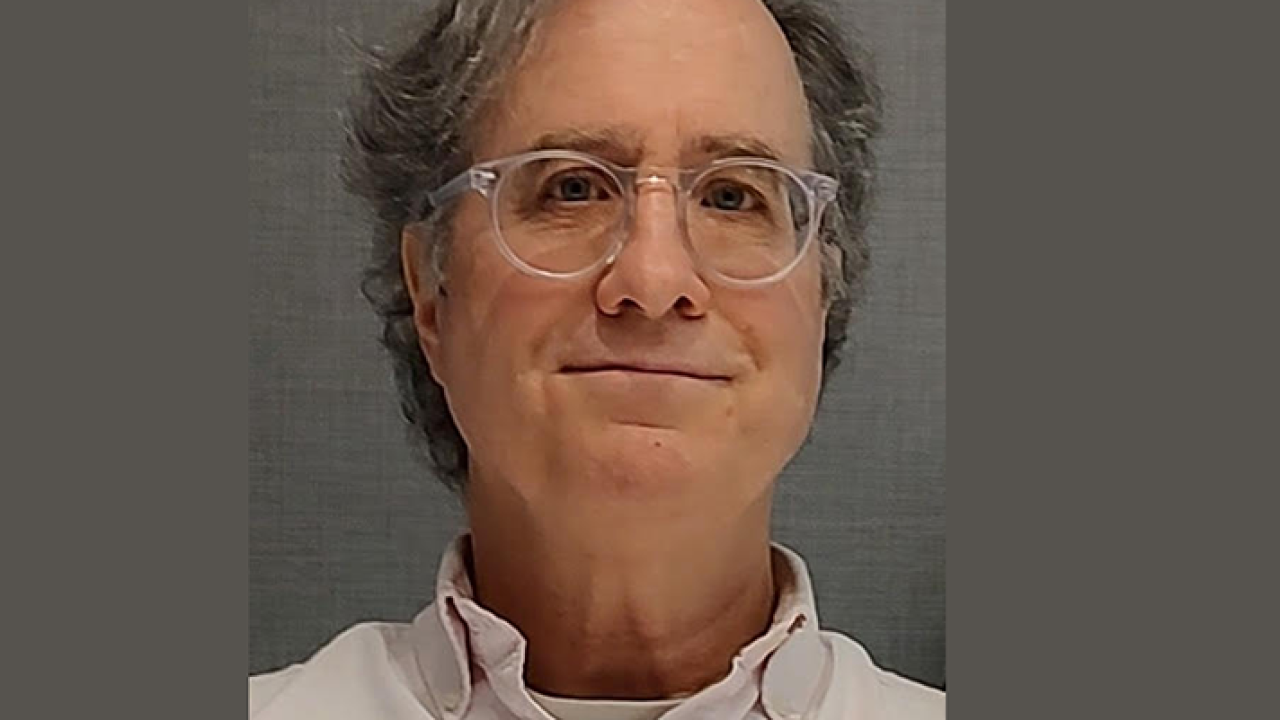

“The question is, do they have to go to the final tier, Tier IV?" said Howard Cure, director of municipal bond research for Evercore Wealth Management. "The [state’s possible] appointment of a financial manager raises questions about just how much authority there would be for the mayor and other elected and appointed officials. That’s always a natural source of frustration and contention between the two.”

MARB rejected a

“Plan adoption will also reduce the city’s financial forecasting by forcing it to develop budgets using realistic projections,” said Moody’s Investors Service, which rates West Haven's general obligation bonds Baa3 -- just above junk -- with a negative outlook.

S&P Global Ratings assigns West Haven a BBB rating, or two levels above speculative grade.

Oversight board chairman and state budget Director Benjamin Barnes said West Haven should restore its fund balance to about 5% of the city budget. The current plan is roughly $162 million. While saying 10% was more desirable, Barnes acknowledged that 5% was more realistic.

"The members were pleased with the progress that was made but have a few more amendments for the plan," Rossi said.

The oversight board also wants West Haven to bolster funding of its local pension systems, curb retiree healthcare obligations and trim future employee healthcare costs, notably for its three fire districts. In its

“I would like to see another iteration of this plan before I feel comfortable supporting it at the full MARB level,” Barnes said.

After council approval, the oversight board's West Haven subcommittee and then the full board would have to sign off.

According to Moody’s, the back-and-forth with MARB highlights the city's challenges in overhauling itself.

“The MARB's insistence on a multiyear financial plan is credit positive for the city, although it will force West Haven to make difficult short-term decisions such as cutting staff or raising taxes,” said Moody’s.

Moody's expects MARB and West Haven to reach a common ground, "Still, those [restructuring] funds would not represent a long-term solution to the city's recurring deficits," Moody's added.

Hartford poses a different dynamic, said Cure.

“Hartford had underfunded PILOTs [payments in lieu of taxes] and the mayor there has a personal relationship with the governor,” said Cure. “Here [in West Haven], they’ve just had trouble getting their arms around their deficits.”

Mayor Luke Bronin was Gov. Dannel Malloy’s chief counsel before his election to the city office in November 2015. The state in March -- under a deal criticized in many corners of Connecticut --

New Haven Mayor Toni Harp has said her city does not intend to apply to join MARB.

West Haven has seen its tax base shrink over the years, largely due to the loss of manufacturing.

German pharmaceutical giant Bayer closed its 113-acre Bayer HealthCare research facility in 2008, only five years after a major facelift. Yale acquired the property for laboratory space, but while the university makes payments in lieu of taxes, the parcel effectively went off the tax rolls.

In addition, the University of New Haven, based in West Haven despite its name, has built out as it morphed from a commuter school to a residential campus. Its $96.7 million bond issuance in April refunded outstanding bank debt related to that development, and its Bergami Center for Science, Technology, and Innovation is scheduled to open next fall.

A proposed hotel along Interstate 95, at the site of a Staples retail outlet that closed in 2002, has yet to materialize.

“There is some development, but you wonder if they would endure another recession,” said Cure.

Transit-oriented development remains a potential. Metro-North Railroad, a unit of New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority, opened a West Haven station five years ago. A hulking tire factory, vacant since the early 1980s, remains a tempting, let elusive, target for redevelopment.

Economic development is still a local quandary, according to David Riccio, who lost the general election to Rossi last November.

“So many development plans of occupancy need to be addressed,” said Riccio, a former council member. “Downtown revitalization has been kicked down the road from administration to administration.”

West Haven, which incorporated as a city in 1961, remains politically divided.

Rossi, a former councilwoman and the city’s first female mayor, won the election with a plurality last fall. She defeated two-term incumbent Ed O’Brien by just 136 votes in the Democratic primary, then beat him again two months later with O’Brien -- who approved the deficit borrowing late in his tenure -- running as a write-in candidate. Republican Riccio was third.

The city’s fiscal situation hovered over a 75-minute public speaking session at the Aug. 27 council meeting despite the absence of the five-year plan from the agenda. Parochial worries included potential asset sales; declining maintenance despite a 22% rise in the budget since 2005; extreme austerity measures such as the removal of two snow days for crossing guards; and an opaque culture at City Hall.

Rossi said her administration is committed to transparency.

“I believe everything should be taped,” said Rossi, who posts recordings of meetings on her Facebook page.

Even amid austerity -- Rossi eliminated 12 positions earlier in the year -- the city could restore confidence in City Hall by beefing up its operations, said MARB board member Patrick Egan. He noted that Rossi, in a prior meeting, admitted she was reviewing job descriptions.

“That’s not a mayor’s job,” said Egan, a former New Haven assistant fire chief and previously president of the New Haven firefighters union.

“To me, the way the city is currently structured from the top down is thin,” Egan added. “There should be a staff in place that makes this city run. And if it costs a little more on the investment end, then that makes me feel more comfortable about giving money to the city.”

Rossi’s executive assistant, Louis Esposito, was doubling up as city public works commissioner for several months until she hired Tom McCarthy for the position. Rossi cut the public works salary to $95,000 from the previous $103,000.

“It’s below market rate, if you will, but we’re a poor town,” she said.

How effectively Connecticut can fix West Haven and other cities, given its own fiscal struggles, remains an open question.

The state’s own problems with repeated deficits shows “how vulnerable the weaker cities are,” said Cure. “If the economy’s weak, the economy’s weak, and then there’s not much the state can do.”