A veto by the New Jersey's governor underscores the debate over the value and effectiveness of the state's business tax incentive program.

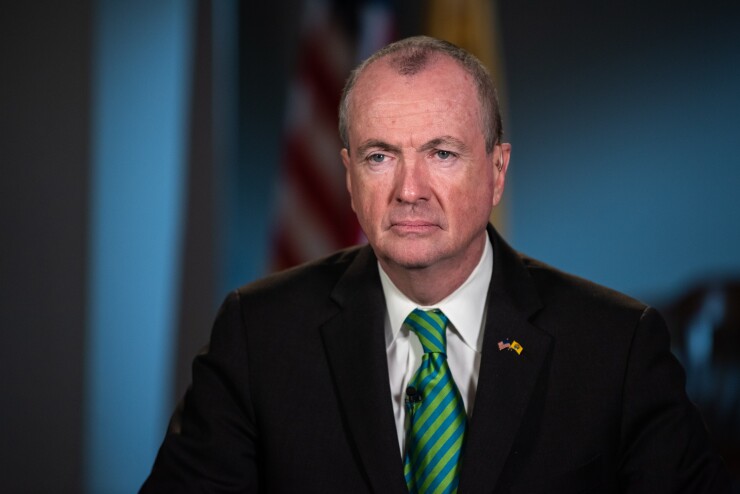

Two incentive programs expired on July 1, and Gov. Phil Murphy vetoed a bill to extend them unchanged until January, saying that major changes were needed to the programs administered by the New Jersey Economic Development Authority.

Murphy's

“For the past six years, New Jersey has operated under a severely flawed tax incentive program that wasted taxpayer money on handouts to connected companies instead of creating jobs and economic growth,” he said in a statement.

Financial experts are warning about flaws in the 2005 legislation that have cost the cash-strapped state billions in revenue.

Lawmakers will now consider whether to try to override the veto, which requires two-thirds supermajority votes in both the Senate and Assembly.

At Sept. 5 hearing of the special Senate Select Committee on Economic Growth Strategies, several economists and policy experts cast doubt about the effectiveness of tax credits. The NJEDA has approved $11 billion in tax breaks for businesses since 2005 with $8.6 billion awarded under the Grow New Jersey Assistance and Economic Redevelopment and Growth Grant programs created under the Economic Opportunity Act of 2013 under former Gov. Chris Christie.

“Evidence suggests that if New Jersey continued its current unusual state of not having any economic development incentive programs and spent that money on other public services instead, it might not be any worse off in the long run,” Jackson Brainerd, a fiscal affairs policy specialist with the National Council of State Legislatures, said during the Senate hearing. “Without proper state oversight of incentive programs, states risk putting themselves in negative budget situations.”

The sharp

A July 2018

Under the EOA of 2013, companies relocating to Camden were given a property tax exemption for the first 10 years and then pay a reduced tax rate for a subsequent 10 years. Professor Michael Lahr, director of Rutgers Economic Advisory Service, said during his Sept. 5 hearing testimony that this aspect of Grow NJ legislation was problematic and did not work in Camden’s favor toward generating needed tax revenues for a long struggling city.

“In distressed areas, this seems like insanity to me,” said Lahr, who co-authored the 2018 Bloustein review on NJEDA tax incentives. “It was a strange piece of math in that legislation.”

A

“The program I’ve outlined in the conditional veto is one that creates good jobs and works for everyone, not just the connected few, and one that will help restore New Jersey’s prominence as the state of innovation," Murphy said in the statement accompanying his veto.

“New Jersey was totally off the charts in terms of the incentives that were offered under Grow NJ,” said Dan Levine, former New Jersey assistant who led many of the Garden State’s economic development efforts. “It has become too much of a zero-sum game.”

Levine, who now advises companies on relocations at Oxford Economics, said two of the main problems with the Grow NJ legislation was too much reliance on equating real estate development with economic development and putting increased weight on a marginal tax analysis. He added that other shortcomings in the measure were the allowance of tax credit transfer sales and the lack of a reasonable cap for awards, which previously was $200 million.

“New Jersey was not being selective in the incentives that were awarded,” Levine said. “New Jersey simply began to put all of its eggs in one basket in that all of its economic development would be driven by tax credits.”

The budget cost of the Grow NJ tax breaks has put the Garden State in a deeper fiscal hole as it grapples with funding pension obligations, transportation infrastructure and public schools, according to Gordon MacInnes, past president of the liberal-leaning New Jersey Policy Perspective. Structurally imbalanced budgets coupled with a steep pension burden contributed to New Jersey falling to the second-lowest bond ratings among U.S. states at A3 from Moody’s Investors Service, A-minus from S&P Global Ratings and A from Fitch Ratings and Kroll Bond Rating Agency.

“It is one of the most extreme examples I have come across of rushed legislation enacted without any sensible development,” said MacInnes, a former Democratic state senator and assemblyman who represented Morris County. “The consequences for the state going forward are going to be bleak.”

The Senate committee is scheduled to another hearing on Sept. 23 that will feature testimony from business leaders who have sought tax incentive applications. Senate committee chairman Bob Smith, D-Piscataway, told reporters after the Sept. 5 hearing that he expects that by the end of the current legislative session there will be “some suggestions for everyone to put together a more effective program.”

The press offices for Murphy and NJEDA did not immediately respond to requests for comment on efforts to formalize new tax incentive programs.