PROVIDENCE, R.I. – Jeff Diehl had just moved to Rhode Island last year when he heard then-Vice President Joe Biden's "Lincoln Logs" reference to the crumbling East Shore Expressway Bridge in East Providence.

“As a new resident, frankly I took a little bit of offense to that,” said Diehl, the executive director of the Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank. “But it didn’t stop me from looking at what was needed here in the state in terms of improving infrastructure.

“A lot has been done since then.”

The infrastructure bank, founded 18 months ago, finances Ocean State projects through bonds, loan origination and grants, while mobilizing for sources of public and private capital.

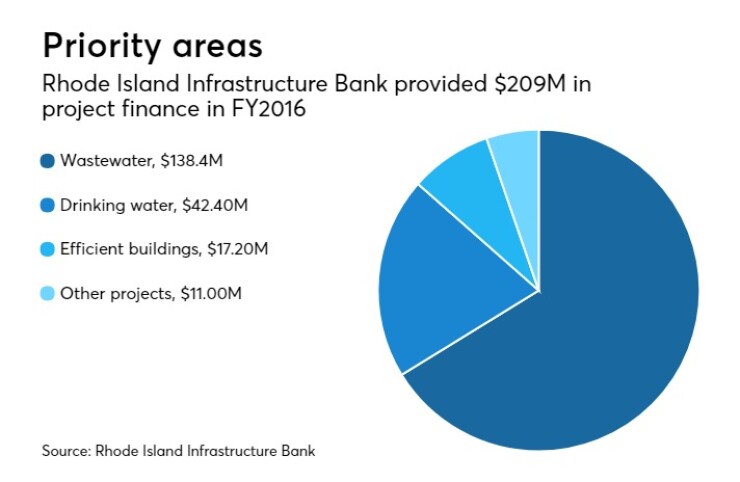

Across all programs in fiscal 2016, the bank provided $209 million in project finance to municipalities, water and sewer utilities and quasi-state agencies, marking a 269% increase from the $56.6 million in project finance the previous year.

Its inaugural summit Tuesday at the Omni hotel in downtown Providence drew a larger-than-expected 350 people. Topics ranged from economic development to resiliency to school construction.

“It’s a subject that’s important to people here in Rhode Island,” Diehl said in an interview. “They understand the importance of it from not only an economic point of view but also on a climate and environmental and a jobs perspective.”

Other state initiatives include the RhodeWorks transportation improvement campaign and the hiring of a chief resiliency officer, Shaun O’Rourke, director of stormwater resiliency at the infrastructure bank. The state has 400 coastline miles and 21 of its 39 communities are coastal.

The Rhode Island economy has improved of late. Its unemployment rate, at or near the bottom nationally a few years ago, is now up to 31st among the states at 4.3% in August, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

State officials just broke ground on the Wexford Innovation Center on Providence land vacated by the relocation of Interstate 195 and corporate relocation expert John Boyd Jr. said at the conference luncheon that Rhode Island has a fighting chance of making the short list for retail behemoth Amazon’s planned second headquarters.

Infrastructure, however, is a different story. An American Society for Civil Engineers scorecard rates Rhode Island last in the country with 56% of its bridges obsolete.

The organization also said more than half the state’s roads are in poor condition, tying it for last nationally.

“A lot of what we’re going to be doing in the near-term is figuring how we can make that scorecard better, and how we can make more parts of the state desirable for companies to come in and either expand their operations or locate new operations and put people to work,” said Diehl, a Michigan native and former executive at HBC and Strategic Sovereign Advisors.

Business-climate rankings often emphasize infrastructure quality, according to state General Treasurer Seth Magaziner.

“When you actually big down into the data and what goes into these rankings, where Rhode Island doesn’t always compare favorably, infrastructure is always listed as one of the areas where we are lagging the most,” said Magaziner, who has widened the bank’s focus from its original mandate to include such programs as a revolving efficient buildings fund.

“If you drive the country, in the states where their economies are improving and you see the quality of their roads and the quality of their school buildings, you know that they understand that high-quality infrastructure is necessary if we are going to have a competitive economic climate.”

Roughly two-thirds of the bank's financings in fiscal 2016 backstopped wastewater initiatives. Drinking water and building energy efficiency also took priority.

Infrastructure extends well beyond traditional roads, rails and bridges, said Mark Huang, the Providence director of economic development.

“Today, with advances in numerous technologies, whether clean tech or digital, it’s ‘smart city,’ ” said Huang, citing 220-volt chargers for hybrid vehicles, LEED street lights and better sensors.

Political leaders often shun the down-and-dirty projects because they’re less glamorous, said Tim Sullivan, deputy commissioner for Connecticut’s Department of Economic and Community Development and a former operative in New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration.

“The great political leaders of our time are the ones who have the tenacity and the wherewithal to say ‘Yeah, I’m going to invest XYZ millions or billions of dollars for something that might not come out of the ground for five, 15 or 25 years and might even never come out of the ground,'” said Sullivan.

“[Bloomberg] spent $8 billion of city money to complete a third water tunnel to connect water up in the Hudson Valley down to New York City," he said. "There couldn’t be a less sexy, less PR, less political upside product in the world. But New York City has the second-tastiest water in America.”

Corporate relocation consultant Boyd said three mobile sectors – corporate headquarters, logistics and banking and finance – are already well-represented in New England.

“Expect a new wave of projects in the months to come,” he said. Labor and real estate costs are lower in Rhode Island, said Boyd, who praised Gov. Gina Raimondo for her jobs-creation and pension-overhaul initiatives.

“My advice to politicians is to do the heavy lifting first. Do pension reform. Lower taxes. Then incentives won’t be so difficult.”

As if Rhode Island doesn’t have enough on its plate, a report by consulting firm Jacobs Engineering, commissioned by the state’s School Building Authority, said the state must spend $2.2 billion to upgrade its school buildings to a suitable condition. That figure could spike to $4 billion over 10 years.

It also forecast $628 million in high-priority construction and repairs necessary to keep students and teachers “warm, safe and dry in their classrooms.” Within that figure, $54.5 million were considered top-priority deficiencies such as building safety or code compliance.

Providence, the capital city and the state’s largest school district, had the greatest facility deficiency cost of $372.4 million. Pawtucket and East Providence had the largest deficiency costs per square foot at $160 and $152, respectively.

Raimondo commissioned a task force, which Magaziner and Commissioner of Elementary and Secondary Education Ken Wagner will co-chair.

“No parent should have to worry when they send their kid to school in the morning about whether their kid is going to be safe in that school,” said Magaziner. “This is 2017. We should be past that.”

Magaziner expects to complete a plan by the end of the year.

“It's a big task,” he said. “People think it’s crazy that we’re going to find a way to fix all of our schools by December, but I have not been more excited about any project since I took office two-and-a-half years ago, because we have to do it.”

The fixes involve more than mere buildings, said Joseph da Silva, head of the School Building Authority, which operates under the state’s Department of Education. Children, he said, learn better in a cleaner environment.

“These are powerful spaces,” he said. “Those buildings shape their identities, what they do on a daily basis and how they act.”

Diehl acknowledged the busy slate that awaits for the infrastructure bank.

“We’re going to continue to work with our partner departments across the government to figure out how we can bring more investible funds into these projects and bringing in the private sector as well,” he said.

“That’s what we’ve really been about, and figuring out how we can look at infrastructure as a strong economic development tool.”