LOS ANGELES — When is $73 billion not enough? When it is compared to the capital needs of California public schools, say school construction advocates.

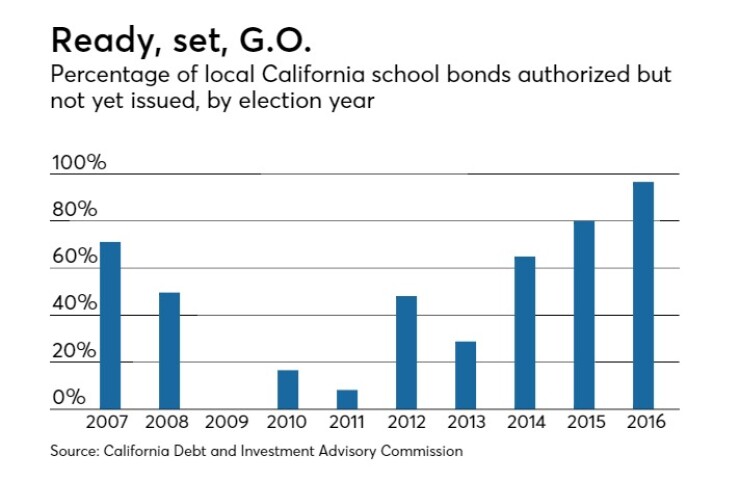

California school and community college districts have $64 billion of local voter-approved but unissued general bond authorization.

Combine that with the $9 billion state school bond measure that passed in November and it sounds like districts have an admirable war chest to tap to build new schools and repair existing buildings.

But “industry benchmarks suggest the state’s K-12 school districts should spend nearly $18 billion a year to maintain their inventory, ensure buildings are up-to-date, and to build new spaces to handle enrollment growth,” according to a September 2016 study from the University of California, Berkeley Center for Cities + Schools.

Nearly half of the state’s school districts underspend on maintenance and operations, raising educational and health equity concerns, said Jeffrey Vincent, who co-authored the UC Berkeley report and is deputy director of the center.

The underinvestment in California’s public school facilities raises questions as to whether or not the buildings are safe and healthy, Vincent said.

It might also be a factor in the state’s difficulties in attracting and retaining teachers, he said.

Nearly a third of the state’s teachers are approaching retirement and the Center for the Future of Teaching and Learning estimates that schools need to hire an additional 100,000 teachers over the next 10 years to fill the gap.

The $64 billion in unissued general obligation bonds includes $30 billion approved by voters for local school construction in November’s election, according to a

It is hard to determine how far that money and the $7 billion from the state bond measure earmarked for K-12 schools will go toward the state’s school building construction needs, Vincent said.

The state doesn’t have a database cataloguing how many school buildings there are in the state or what state of repair, or disrepair, they are in, Vincent said.

The studies done by Vincent’s policy and research group on school facilities estimated how much the state needs to spend using methods private industry and the federal government use to calculate the cost to adequately maintain buildings. They compared actual school facility spending each year against building-industry standards for minimum spending needed to keep buildings safe and functional.

One of the metrics was to look at bond issuance, Vincent said. They found the state spent up to $1 billion a year between 1998 and 2012 for a total of $35 billion, before the state’s previous school bond authorization was depleted in 2012. Spending of local bonds during the same time frame totaled $66 billion. Schools spent another $10 billion for developer fees, for a total of $115 billion on the capital side.

There could be a number of reasons schools with such great facilities needs have not issued bonds including economic changes or unexpected declines in enrollment. But given the number of school districts that floated bond measures – and used the fact locals would need matching funds for a cut of the state’s $9 billion bond in advocating for those measures – the state’s delay in getting voter approval to replenish the program is certainly a factor, Vincent said.

Voters approved Proposition 51 with a 55% majority.

Gov. Jerry Brown opposed the measure, contending that the current system for allocating state bond funds is rigged to favor larger, well-heeled school districts over smaller districts that need the help more.

A line for the money in Proposition 51 has already formed – partly from the pent-up demand left over from the depletion of the 2006 bond authorization.

The state has certified $370 million in applications for state matching funds on new construction and maintenance projects and another $1.6 billion in applications have been submitted, said H.D. Palmer, state Department of Finance spokesman.

“We were very disappointed with the May revision (to the governor’s proposed budget),” said David Walrath, an education lobbyist and the president of Murdoch, Walrath & Holmes Inc. “The DOF is proposing issuing $600 million in bond sales a year and we already have $2 billion in applications at the state level.”

At that rate, he said, it could be 2027 before the state issues all of the bonds in the measure.

“We think the state should issue $1 billion per bond sale for spring 2018, fall 2018 and spring 2019,” said Walrath, a legislative advocate for the California Coalition for Adequate School Housing.

It flies in the face of what the state said in terms of working with smaller school districts that couldn’t pass bonds, Walrath said.

“We don’t see how delaying projects makes any sense, particularly in an increasing interest rate environment,” he said.

Palmer points out that the state has a variety of other programs it issues bonds for – and the market can only absorb so much during its annual spring and fall sales.

“Twice a year we survey what the relevant needs are with all of the agencies,” Palmer said. “Then we work in concert with the treasurer’s office to determine the size of our offering.”

The governor also has built his reputation on paying down debt and being reluctant to take on more.

Some school district clients of Fieldman, Rolapp & Associates, a California financial advisory firm, are concerned about inflation if the state delays pushing out its matching funds, said Adam Bauer, the firm’s chief executive officer. Taxpayers who voted for the bonds want to know why they aren’t seeing projects start, Bauer said.

“Districts are adjusting their budgets, because if the state money doesn’t flow to them, they have to adjust for inflation,” he said. But some districts moved forward on projects hoping the state would refund the cost, Bauer said.

That could be a problem for the $1.7 billion in applications that have not been processed by the state.

The State Board of Education might ask people to resubmit applications – and there are some districts that have not submitted applications for matching state funds for construction projects, Palmer said. The board is expected to take action on the issue before July 1, he said.

CASH is not happy with the proposal, Walrath said, because voters approved the bonds based on the existing system. Traditionally, the state has issued matching funds on a first-come, first-serve basis, which has been more favorable for larger districts. Districts with less affluent tax bases have had more difficulties coming up with the 50% match needed to qualify for state money, Vincent said.

He suggested a better system would be to have a sliding scale similar where districts with less affluent tax bases have to provide a 20% match to the state’s 80% match and maybe the reverse for more affluent districts.

The Department of Education has been looking at ways to make the process less onerous for smaller schools whether it’s by acting as an ombudsman for those districts or some other method of leveling the playing field.

Brown slowed issuance of the bonds as part of his budget legislation saying he wanted the Office of Public Instruction to establish better auditing procedures. A 2016 Department of Finance report criticized the Office of Public Construction for not fixing problems uncovered in a review of audits on $7.3 billion in bonds that were authorized by voters in 2006 in Proposition 1D.

The report was a follow-up to a June 2011 review of the Office of Public Construction’s procedures. Half of the six recommendations made by DOF in 2011 had not been implemented, according to the 2016 report.

As of September 2015, 1,533 projects representing over $3 billion in Proposition 1D bond proceeds had been closed without an audit to determine whether the money was spent in line with the bond measure’s requirements, according to the June 2016 report.

DOF conducted a limited audit of 19 Proposition 1D projects at 10 school districts. The limited audit found the districts had inappropriately used $3 million in bond funds to purchase such items as a Chevrolet truck, two tractors, four golf carts, iPads, athletic uniforms, a mascot uniform and custodial/cleaning supplies.

The state is considering a program that would require school districts to provide the Office of Public Construction with information included in their audited financial statements tracking what bonds are spent on.

Bauer said the school districts are already required to provide that information to the citizen bond committees that oversee bond programs – so it isn’t adding a new requirement.

“We just want to make sure the money is being spent on what voters intended it be spent on – new school buildings or modernization,” Palmer said.