Age, record usage and years of deferred maintenance have caused serious infrastructure problems at New York City’s parks, according to Center for an Urban Future.

“While many New Yorkers are familiar with the city’s aging streets, bridges, subways, libraries and schools, there is little awareness of the age and infrastructure challenges facing the city’s public parks,” said the 52-page

It says that the average city park is 73 years old, and that parks in every borough are struggling with aging assets at or near the end of their useful life — including drainage systems, retaining walls, and bridges.

“For decades New York City has provided too little money for basic maintenance and too few staff -- including, plumbers, masons and gardeners – to keep critical park assets from deteriorating and mitigate problems before they grow,” said the report. “Much more will need to be done.”

Unseen infrastructure such as draining systems, retaining walls and waterfront structures pose imminent threats, the report said.

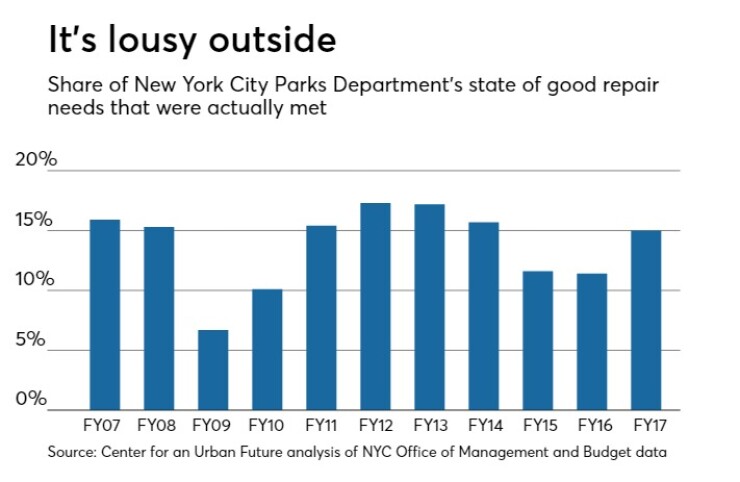

The Stavros Niarchos Foundation funded the report, which finds that the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation’s official state-of-good-repair needs, which includes major infrastructure and capital repairs, increased by 45% over the past decade, to $589.1 million in fiscal 2017 from $405.9 million in fiscal 2007.

Meanwhile, the department’s recommended maintenance needs increased by 143%, to $34 million from $14 million. Yet, just 15% of the recommended state-of-good-repair needs, and 12 percent of the maintenance needs, were funded in the most recent year.

The report listed 21 ideas for revitalizing the parks. It called on Mayor Bill de Blasio to make parks infrastructure investment a second-term priority.

Other suggestions included a sustained capital funding stream; innovative revenue sources such as value capture; a citywide conservancy to raise funds for neighborhood projects; a citywide parks board dedicated to long-term planning; data gathering; cooperation among agencies and an interagency green lab.

“This administration has invested in strengthening the city’s parks system from top to bottom,” said Crystal Howard, the parks department’s director of media relations.

According to Howard, capital programs including the $318 million, 65-park community parks initiative and the $150-million anchor parks project are bringing “the first structural improvements in generations” to sites from playgrounds to large flagship parks.

“Further, as the CUF report notes, Commissioner [Mitchell] Silver’s streamlined capital process is bringing these improvements online faster,” Howard said. “Initiatives like the newly funded catch-basin program and an ongoing capital needs assessment program will ensure that NYC Parks needs are accounted for and addressed in the years to come.”

City Council member Mark Levine, whose district encompasses northern Manhattan, cited the 2005 collapse of a century-old retaining wall in the Washington Heights neighborhood. It snarled traffic and ignited years of confusion over who should pay the bill.

“Nobody knew what a retaining wall was,” said Levine. “Then the one collapsed in Washington Heights, and everybody wanted an inspection.”

Many people interviewed for the report feared other collapses similar to the one in Washington Heights and underneath the Gowanus Expressway in May 2017.

According to the report, estimated capital costs for parks walls is more than $42 million between FY18 and FY21. “However, that cost may significantly underestimate the extent of this [problem], and what it could cost the city in the long term.”

Resilience expert Alan Rubin urged de Blasio’s administration to tap the green-bond market.

“They’re still not using the most common financing vehicle for this kind of work, green bonds,” said Rubin, a principal in the government-relations unit at law firm Blank Rome LLP in New York. “The Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget doesn’t want to do it. I’m hopeful they can use it, because it’s the most efficient way to establish this structure.”

The report cited the best-practices of Minneapolis, Philadelphia, Dallas and Denver as examples for New York to follow. Positives in those cities, according to the study, include sustainable parks plans, long-term funding streams, green infrastructure, citywide foundations and data-driven management.

Rubin said the city should use the request-for-proposals process more broadly.

“They can use RFP for park concessions to look for procurements that are more interesting rather than water or ice cream. There are vendors willing to do work that’s sustainable.”

Rubin also called for setting aside some capital construction discretionary funds for the five borough presidents, who could appoint local coordinators and also leverage funds to obtain federal money.

“We’ve always said getting community buy-in for Smart Cities-type of initiatives is important,” he said. “The borough presidents could then interact with their congressional delegations -- people like Joe Crowley and Hakeem Jeffries.”