Editor's Note: The Pension Crisis — Part 4 of 4

Part 1:

Part 2:

Part 3:

Detroit left a bitter aftertaste for bondholders.

Under the city's plan to shed $7 billion in debt, Detroit reached settlements with its pensioners that left intact public safety monthly checks and cut 4.5% for general employees. Their cost-of-living increases were reduced or eliminated. They did see a big cut in the form of retiree health-care benefits, which were trimmed by nearly 90%, allowing the city to shed a $4 billion obligation.

Unlimited-tax general obligation bondholders, meanwhile, agreed to a 26% cut - with the money going to pensioners - and limited-tax GO holders took a 66% cut. Holders of $1.5 billion of certificates of participation saw a 14% cash recovery as well as a groundbreaking package of vacant land, asset leases, and development deals.

Former U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Steven Rhodes who oversaw Detroit's historic Chapter 9 called the city's plan of adjustment reasonable, fair and equitable, key benchmarks under federal bankruptcy law. The decision to treat its pensioners more favorably than other creditors was fair and justified in part because of state constitutional protections of the retirement obligation, Rhodes said.

The treatment Detroit's bondholders relative to pensioners was typical, as pension funds have flexed political muscle in bankruptcy cases across the nation. As bankruptcy specialist David Dubrow of Arent Fox LLP put it in a published piece:

"While bondholders, pensioners and workers can all be impaired in a bankruptcy as a general matter, public policy and politics determine outcome more than any other factor given the limited legal precedents in Chapter 9."

In California, the Vallejo, Stockton and San Bernardino bankruptcies all pitted the bond investors – whether they held pension bonds or other bonds – against the nation's largest pension fund, the mammoth California Public Employees' Retirement System.

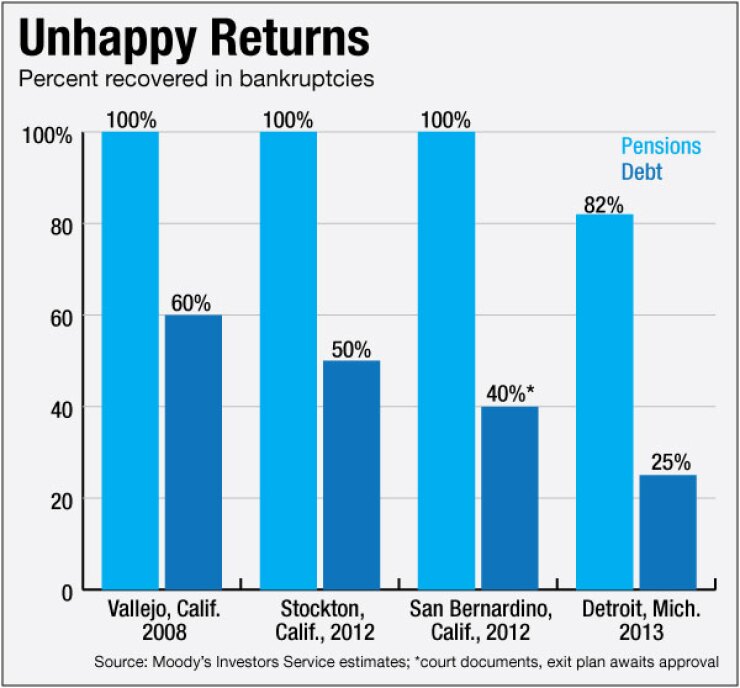

While California's pension funds received a 100% recovery in the trio of bankruptcies, bondholders did not fare as well. In California, bondholders received anywhere from a 40% to 60% recovery, though San Bernardino's bankruptcy plan has yet to be approved.

In Detroit, the pension funds received an 82% recovery, according to a 2015 Moody's Investors Service report, while bondholders received only 25% on a "weighted-average basis" that factored in the impact on LTGO, ULTGO, and COP holders.

Behind the protections built into Detroit's exit plan for pensioners was the city's so-called "grand bargain." A philanthropic consortium collectively pledged $366 million to offset the city's massive pension burden and avert any move to sell off the assets of the city-owned Detroit Art Institute museum.

The funds leveraged support from corporations and the state to bring the package to more than $800 million and in turn brought the city's public unions to the table to agree to concessions. The funds are to be set aside over a 20-year period and handled by special entity that will direct them to pay benefits.

Under the plan, the state also agreed to provide $195 million to Detroit pensioners in exchange for pensioners dropping the right to sue the state to recover the unfunded pension debt that the city cannot pay. That debt could have been as high as $3 billion. The pension restructuring is central to the city's recovery plan, as it was freed of the need to make pension payments for 10 years as well as the liability for other post-employment benefits, or OPEB.

"The most emphatic message of the Detroit and Stockton plans of adjustment is their intent to protect work force sustainability at the expense of bondholder repayment," Fitch wrote in a special report on those bankruptcy outcomes.

"In each case, the bankruptcy judge agreed that this goal was more important than repaying investors. The issue then becomes one of public policy rather than legal constraint, and it appears likely that many governments would similarly favor retaining pensions over the good faith of bondholders."

Detroit's bankruptcy contributed to the burgeoning debate over the potential cracks in general obligation pledges and the use of statutory liens for GO bonds to strengthen bondholders' positions in a municipal workout.

But the politics behind cutting a public employee's benefits remain a strong deterrent for elected officials and courts. At the same time, there's also been a growing discussion of the use of a bankruptcy threat to get labor unions to the table as a distressed municipality looks to cut.

"The standing of bondholders versus pensioners in a municipal bankruptcy can be ambiguous because pensioners may have additional legal and political protections that are superior to bondholders. A municipal government wrestling with politically difficult pension funding or reform may therefore have an incentive to accelerate bankruptcy primarily to reduce its debt," Moody's Investors Service said in the municipal bankruptcy report last year.

Steps taken by California in the wake of its trio of Chapter 9 bankruptcies over the past several years have given bondholders some reassurance when it comes to general obligation bonds issued by cities, but left investors wary about pension obligation bonds.

Pension liabilities – and pension obligation bonds issued to deal with that liability — were issues in the trio of California bankruptcies and in Detroit as well.

In Stockton, Franklin Templeton continued to fight the city for a better recovery even after the bankruptcy judge approved the city's exit from bankruptcy. The company said in its court filings that the bankruptcy court that confirmed Stockton's plan erred in approving a plan that was "discriminatory and punitive" to Franklin, paying it roughly 1% on $35 million of bonds while leaving pensions untouched and paying other creditors who had settled with the city earlier between 52% and 100%.

Stockton's attorneys said in their own filing that Franklin's total recovery rate on secured and unsecured claims is roughly 17.5%. The city countered that any further relief awarded to Franklin would fall squarely on the city's residents in the form of "reduced services, infrastructure investment, and essential reserves."

Franklin finally announced in December 2015 that it would not pursue further appeals in Stockton's bankruptcy.

In San Bernardino, City Attorney Gary Saenz said in April of the agreement with pension obligation bondholders that the city was able to give the bondholders 40% of what is owed, rather than the more severe 1% originally proposed, because the agreement allowed them to stretch out payments 20 years.

The city has drafted a 20-year business plan that found it would be able to feasibly make those payments without the city ending up in bankruptcy again down the road, he said.

"One thing Judge Meredith Jury will look at is the feasibility of the confirmation plan," he said. "We believe we found a model that is dependable."

The pension obligation bond agreement continues a trend of bonds faring worse than pensions in Chapter 9 cases.

Under the settlement, COMMERZBANK Finance & Covered Bond S.A., formerly Erste Europäische Pfandbrief-Und Kommunalkreditbank AG, and municipal bond insurer Ambac Assurance Corporation, agreed to drop their opposition to the city's bankruptcy plan.

The holders of $50 million in pension obligation bonds will receive payments equal to 40% of their debt on a present value basis, discounted using the existing coupon rate, according to city officials.

Though San Bernardino reached an agreement with bondholders earlier this year in its bankruptcy, its bankruptcy exit plan is slated to be voted on in September by creditors. The current hope is that the city could exit bankruptcy by October – if creditors approve the plan and the bankruptcy judge deems the plan good enough to prevent the city from returning to bankruptcy court down the road.