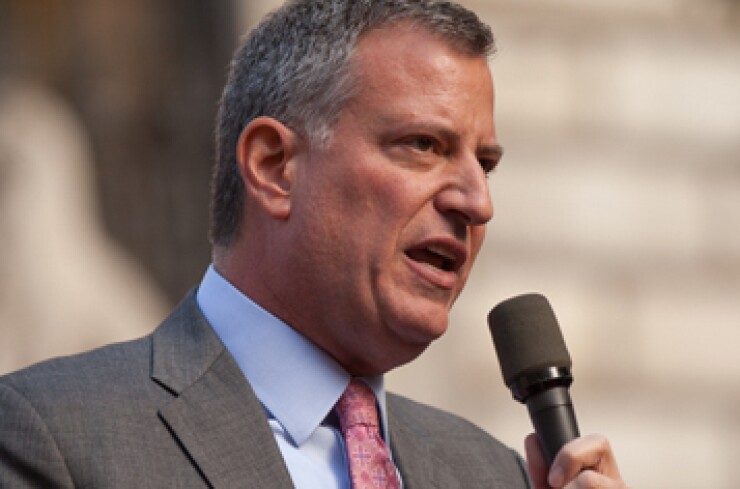

Expired labor contracts and soaring city health care premiums await Bill de Blasio, but for New York's incoming mayor, controlling the city's finances will involve much more than those two headline-grabbers.

Stagnant economic and revenue growth, escalating debt service, the need for better procurement practices, and managing such money-draining agencies as the Health and Hospitals Corp. and the New York City Housing Authority will consume de Blasio, new city comptroller Scott Stringer and various budget wonks.

De Blasio and Stringer will succeed Michael Bloomberg and John Liu, respectively, on Jan. 1.

"The recent election represented a real mandate for fundamental change and better, smarter budgeting," Stringer told a Citizens Budget Commission conference on the Upper East Side two weeks ago. "We all know the drill. Every year it's the same. The same fire houses, the same child-care slots, the same library hours, they all end up on the chopping block only to be miraculously saved in the nick of time.

"It makes for a great show. But we've been ignoring the biggest challenges: slowing growth, ballooning debt service and labor costs."

Pension contributions and debt service accounted for 11% and 8%, respectively, of the city's $76.5 billion budget for fiscal 2014. The local share of Medicaid under state law consumes a further $6.5 billion, or 8%.

According to Morningstar Inc., a change in actuarial assumptions and methods for all five pension plans during the last actuarial valuation caused the aggregate liability to jump by 54%, leading to a decrease in the funded level to what it calls a "poor" 60.1% from 91.8%.

Jeffrey Sommer, the acting executive director of the New York State Financial Control Board, pegged the city's unfunded pension liability of $92 billion. Although the city pays $2 billion annually on a pay-as-you-go basis, the gap is rising 10% annually.

"Over time, longer than the four-year financial plan, that will crowd out other services," said Sommer.

The five pension funds are the New York City Employees' Retirement System; the Teachers' Retirement System of the City of New York; the New York City Police Pension Fund Subchapter 2; New York City Fire Department Pension Fund Subchapter Two; and the New York City Board of Education Retirement System.

Stringer has said he would discuss expanding in-house asset management as a means of curbing external banking fees with the 58 trustees of the five funds. Others have called for an outright consolidation of the five funds.

Pensions have become a hot-button finance issue nationwide, notably so after federal Judge Steven Rhodes ruled that state constitutional protections would not prevent Detroit from cutting pensions in its Chapter 9 bankruptcy.

Anthony Figliola, the vice president of Empire Government Strategies consulting group in Uniondale, N.Y., said the ruling could give cities the "nuclear option" of cutting pension benefits through bankruptcy threats.

"In Syracuse, for example, Mayor Stephanie Miner can say, 'look at what they did in Detroit, and that's a union town.' It gives cities another tool," said Figliola. Miner, just elected to a second term as mayor of the upstate New York city, refuses to borrow to cover pension shortfalls and has criticized such proposals by Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

Under New York City's rolling four-year financial plan through fiscal 2017, debt service and fringe benefits - the latter, essentially, health-care premiums exclusive of pensions - each figure to cost $1.6 billion more annually, reflecting spikes of 8.3% and 5.8%, respectively. Annual budget growth, however, is only 1.5%.

The city is approaching $10 billion per year in new capital commitments.

"By general measures that the rating agencies and others use to measure whether our debt is appropriate to our income, we're over the limit," said Citizens Budget Commission President Carol Kellermann.

The city's debt outstanding for fiscal 2013, according to CBC statistics, was 8.1% as a share of real property value and 14.3% as a share of personal income. Normal benchmarks for high burden are 5% and 6%, respectively.

Moody's Investors Service rates the city's general obligation bonds Aa2, while Fitch Ratings and Standard & Poor's assign AA ratings. Other primary credits include the Transitional Finance Authority, which the state created in 1997 to extend the city's bonding capacity; and the New York City Water Finance Authority.

Capital investment during Bloomberg's 12 years as mayor totaled $123 billion, compared with $90 billion in the previous 12 years under mayors David Dinkins and Rudolph Giuliani, and $70 billion under Ed Koch's tenure from 1979 through 1990. About half of the capital spending was for education and environmental protection, according to CBC statistics.

Some panelists at the CBC conference urged the city to develop an affordability standard for debt as well as criteria for paying some capital expenses from the operating budget.

"This is a perfect time for a new administration to look at revising the way it approaches its capital budget. We have urged for years that it was time to have a written kind of debt policy that what's affordable, what are the priorities, what's going to drop when times are bad, [and] what's going to drop when times are good," said Sommer.

"We think of the capital budget as funny money, as though it's not real cash. People talk about debt service as though it's a non-controllable source. It's not controllable once you issue the debt, but it is very much controllable before you issue the debt and I think that's a focus that should be more in the city's plan."

The city's Health and Hospitals Corp. and New York City Housing, two social safety-net agencies with huge but less publicized deficits, will also require attention.

HHC projects large gaps for fiscal 2014 and beyond, with cost containment measures as yet identified.

The housing agency, meanwhile, has an estimated operating deficit of $192 million for fiscal 2014. The city allocated $71 million to keep senior-citizen and community centers open, while NYCHA must fill the remaining $121 million gap.

NYCHA's list of capital improvement needs is formidable. Stringer issued numerous reports about broken elevators in housing projects while Manhattan borough president, an office he will vacate on Jan. 1. He has vowed a "top to bottom" forensic audit of the agency as comptroller.

Bloomberg's NYCHA chairman, John Rhea, came under fire after a published report in 2012 said the agency was sitting on $1 billion in federal cash earmarked for security and repairs. Additionally, a Boston Consulting Group study cited "significant challenges, many of which are mutually reinforcing."

Less visible budgetary improvement areas citywide include better project scoping and improved use of technology.

"We have to get granular. Washington's closed and Albany's a bridge too far," said CBC debt panelist Robert Hennelly, a labor consultant and interim program director of WBAI-FM in New York.

Hennelly and others also called for more careful vetting of outside vendors to avoid a repeat of the CityTime project fiasco, in which the cost of a payroll-processing modernization project spiked from $63 million to roughly $700 million, most of it to primary contractor Science Applications International Corp. A federal jury in New York last month convicted three computer consultants, including a former city consultant, of corruption related to the CityTime project.

First on de Blasio's list, though, are new contracts for city workers and teachers. A glimpse of de Blasio's initial budget in late January or early February could tell how far he will go to satisfy a labor demand of retroactive back pay. Full retroactive pay would include three 2% raises for the entire workforce for the 2010-2013 round of bargaining, and two 4% raises for teachers and principals for the 2008-2010 round, with a tab of around $7 billion.

A push-pull between city and labor looms over public employee health-care plans. More than 90% of municipal employees enroll in Group Health Inc. and HIP Health Plan of New York — both units of Emblem Health — with the city paying 100% of the premium cost for GHI and HIP for employees, spouses and families.

"It's unusual. No other municipality provides this level of reimbursement," said Kellermann.

The city could save $535 million in fiscal 2015 by requiring city employees and retirees to contribute to health insurance costs, according to the New York City Independent Budget Office, and save a further $316 million by pegging health insurance reimbursement to the lowest-cost carrier.

But tussling with unions will be difficult. Bloomberg essentially punted the matter to his successor.

"On the East Coast and the West Coast, unions are alive and well. Not in the Midwest, not in the South," Philadelphia's city treasurer, Nancy Winkler, said at the CBC conference.

"The consulting and analytic prowess of unions is substantial. It's a continual challenge for all of us, for cities across the country," she said.

"None of this is easy," said Stanley Litow, vice president of corporate citizenship and corporate affairs for IBM Corp., and a CBC trustee. "That's why they call it work."