On May 15, the Senate Finance Committee released the sixth in its series of papers compiling federal tax-reform options.

This latest paper, on community and economic development and prepared without any consultation or coordination with states and local governments, will be the only report directly focusing on options to address financing the nation’s infrastructure.

Twelve days later, the Skagit River Bridge in Puyallup, Washington, collapsed — not only sending three people into the frigid waters below, but also severing the major artery between the West Coast and Canada.

With the nation’s state and local governments already financing some 75% of America’s public infrastructure and the federal surface transportation program on the brink of insolvency, the Finance Committee paper is a recipe for undermining the single most critical source of financing the nation’s public infrastructure.

The paper notes “some believe that it is not an appropriate role for the federal government to assist state and local governments by, for example, helping to pay for local infrastructure or services.”

That, in a statement about top-down federalism, renders unclear just what responsibility a nearly insolvent federal infrastructure role should take, but it clearly leans towards undercutting the bonds issued by states and local governments to finance the bridges, ports, roads, and airports so vital to the nation.

Rather than offering a solution, the paper offers options to aggravate the problem and increase the cost of rebuilding the bridges that tie the nation together.

Unsurprisingly, there is no mention in the Senate Finance Committee paper about the appropriateness of state and local subsidies for the record issuance of federal bonds — bonds not issued to finance investment in the nation’s public infrastructure, but rather increasingly to pay its interest on the national debt.

There are 66,749 structurally deficient bridges and 84,748 functionally obsolete bridges in the United States, including Puerto Rico, according to the Federal Highway Administration — about a quarter of the nation’s 607,000 total bridges.

The Skagit River Bridge was among 11% of U.S. bridges categorized as structurally deficient, according to the 2013 infrastructure report card by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

The group estimated that the federal, state and local governments need to spend $8 billion more a year to catch up with $76 billion in unmet needs for deficient bridges.

Casey Dinges, senior managing director of the civil engineers, notes that of 600,000 bridges in the nation, 150,000 or 25% are either “structurally deficient” or “functionally obsolete.”

But with the federal government hobbled by a sequester — with another nine years to run — and its own Highway Trust Fund nearing insolvency, the burden of rebuilding the nation’s bridges is falling increasingly on state and local finance. That task in itself was made more expensive by the decade-long application of the federal sequester to so-called Build America Bonds.

Through the issuance of general obligation and revenue bonds, state and local governments have been reducing that backlog, but slowly.

Spending by states and local governments on bridge construction adjusted for inflation has more than doubled since 1998, from $12.3 billion to $28.5 billion last year, according to the American Road and Transportation Builders Association — an all-time high.

State and local governments issued $55.3 billion in transportation bonds in 2012 according to Thomson Reuters, binding and bonding themselves to long-term commitments to the nation’s infrastructure.

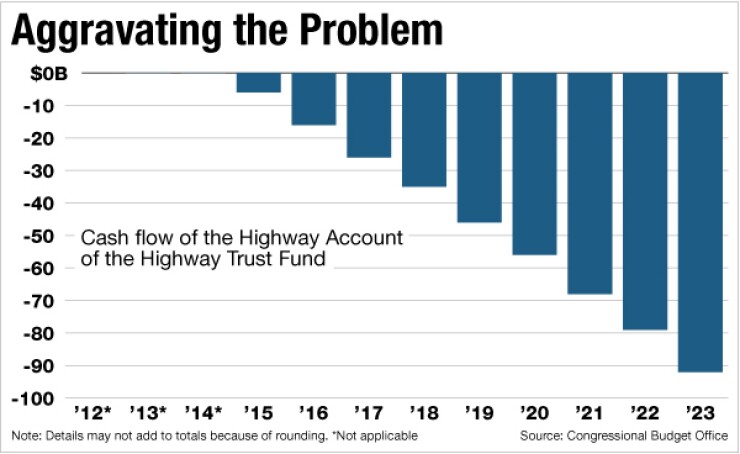

In contrast, the Congressional Budget Office projects that starting in 2015 the highway account of the Highway Trust Fund will have insufficient revenues to meet its obligations, resulting in steadily accumulating shortfalls.

That projection is based on two assumptions: that the taxes whose receipts are allocated to the highway account will continue at their current rates (most of them are scheduled to expire at the end of September 2016) and that federal funding for highways will increase at the CBO’s projected rate of inflation.

To avoid such shortfalls, Congress would have to enact legislation to reduce highway funding, increase dedicated tax receipts, transfer money from the general fund of the Treasury to the Highway Trust Fund (as has occurred in recent years), or undertake some combination of those approaches.

MAP-21, the long-awaited, two-year federal surface transportation authorization bill passed by Congress last summer, included many key policy changes long sought by state governments that are now being implemented.

However, the new law lacked an essential ingredient: revenues.

Instead, Congress had to syphon off general fund dollars to shore up the Highway Trust Fund just to reach October 2014, when the law expires. The trust fund itself is getting by on fumes: federal gas-tax revenues have been dwindling in recent years due to increased fuel efficiency and other factors.

Now federal transportation programs are subject to the sequester. Perhaps the idea is to sequester every bridge in America. Indeed, as can be seen above, under the CBO’s baseline projections, the highway and transit accounts of the Highway Trust Fund will have insufficient revenues to meet all obligations starting in fiscal 2015. Under current law, the fund cannot incur negative balances and has no authority to borrow additional funds.

The Finance Committee paper, in its section on state and local finance, offers these options: repeal of state and local tax exemption, elimination and replacement of tax exemption with a “new, permanent direct subsidy for bonds for financing governmental capital projects,” replacement of the (interest) exclusion with a direct subsidy, or a phase-out over (“for example”) three years.

So, in a series of suggestions, the federal ability and willingness to provide contributions to rebuilding the Skagit River Bridge have been subjected to sequester and face insolvency.

The paper options would all increase the cost to state and local governments — and tax and ratepayers — to finance Interstate highway bridges critical not just to public safety but also to international trade.

Perhaps equally disconcerting, they would undercut the certainty of 30-year financing so vital for the efficiency of the American municipal bond market. Instead, it would be replaced it with a system where state and local governments, along with investors, would have no way of knowing from one year to the next what interest obligations they would have to meet.

Meanwhile, drivers and trucks carrying on the commerce of the nation are left unsure whether or not they might be on a bridge to nowhere.