Some banks are taking a detour around the complicated and expensive process of guaranteeing a municipal government’s bonds by just buying the bonds themselves.

Writing a letter of credit or standby bond-purchase agreement on a local government’s debt subjects banks to a web of regulations and capital requirements that are only becoming more restrictive with time.

According to market sources, some banks have discovered that simply taking on an issuer’s bonds for their own portfolio is a cheaper and less onerous way to extend credit than the types of bank facilities that were in vogue last decade.

While no measure of this type of financing exists because municipalities do not have to disclose when a bank takes on its bonds, sources say it is definitely growing.

“Some local governments looking to tap the market are finding that things have changed since they last sold bonds,” said Bill Rhodes, a partner in Ballard Spahr’s public finance practice. “Some of these banks are coming to them and saying, 'We’re willing to buy and hold your bonds.’ … Instead of issuing a three-year letter of credit, they’re just buying and holding the bonds for three years.”

Anyone getting too excited about this should be forewarned that this is probably not the cure-all that municipalities with short-term funding troubles are looking for. For one thing, several experts are skeptical about just how much of this load banks are going to carry. Second, a bank taking on a municipality’s remarketable debt for three years solves its funding troubles for exactly three years — not forever.

“I don’t know that that’s going to be an overwhelming trend,” said John Hallacy, director of municipal research at Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

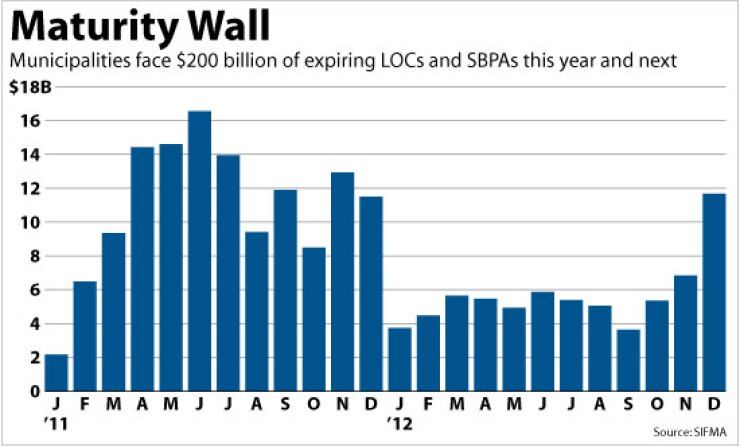

Municipalities face a $200 billion wall of expirations on bank credit facilities this year and next, according to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, with a daunting spike beginning next month and lasting through July.

These facilities support variable-rate demand obligations, which are nominally long-term paper that changes hands at regular short-term intervals in a remarketing that resets the interest rate.

In order to appeal to investors in short-term markets, namely money market funds, VRDOs typically carry a put option, granting the holder the right to sell the bonds back to the issuer at par whenever he wants.

That’s where the bank comes in.

Someone needs to buy the bonds from the investor when he exercises the put option. Banks promise to be that buyer, for a price. According to a Moody’s Investors Service report distributed Tuesday, municipalities can expect to pay anywhere from 50 to 150 basis points for this type of guarantee. Before the credit crisis, this type of liquidity was available for 10 to 25 basis points.

The mountain of expirations in 2011 and 2012 could hardly have come at a worse time. A handful of banks that used to be active in this market have either withdrawn voluntarily or were cast out by the rating agencies.

It also coincides with the unveiling of the Basel III framework, which imposes more stringent capital requirements for these types of facilities beginning in 2015.

The biggest burden for banks from Basel III is the 100% “liquidity coverage ratio” — a requirement to hold in cash or Treasury bonds the amount of money the bank would need to honor its liquidity guarantees if they were all exercised simultaneously. This effectively means that to guarantee a $1 billion variable-rate municipal structure, the bank needs $1 billion in cash.

So if the bank needs the entire par amount on hand anyway, why not just buy the VRDO?

“In some cases, it may prove less costly for the bank and its client to use a fully funded loan instead of an LOC or other backstop,” JPMorgan analysts Chris Holmes and Alex Roever wrote in a report last week.

According to Rhodes, in this type of arrangement the bank offers to take on the VRDO from an issuer with an expiring liquidity facility. The parties negotiate an interest rate, which is typically a short-term index plus a fixed spread. The bank holds the debt for a certain term, perhaps three to five years.

Aside from sidestepping capital and liquidity regulations, the primary benefit of the process just described is the cost. Municipalities don’t need to pay a remarketing agent or an underwriting fee, since the buyer of the bond is the underwriter. The rapidity with which these transactions can take place also means lower costs for legal counsel, Rhodes said.

“The time, money, and political aversion involved in preparing official statements and paying lawyers and underwriters are not trivial in times of stressed politics and finances,” Holmes and Roever wrote.

There are two caveats.

One is that it is merely a temporary reprieve. At the end of the term of the bank loan, the municipality is right back where it started. One could argue that a bank loan that shepherds a municipality around the 2011-2012 maturity cliff is valuable in its own right, but the fact remains that the government is still scrambling every few years to ensure liquidity for a long-term structure.

“Although eliminating exposure to remarketing risk over the life of the loan, the direct loan alternative exposes credits to the same renewal-market access risks inherent in VRDOs,” a team of Moody’s analysts wrote in a report Tuesday.

The second is that banks are considered unlikely to do this enough to be much of a savior for a $400 billion VRDO market.

Holmes and Roever don’t expect direct bank loans to municipalities to be much more than $5 billion to $10 billion this year, compared with more than $130 billion of expiring LOCs and SBPAs. They call some of the recent media coverage afforded to direct bank lending to municipalities “a bit overstated.”