WASHINGTON — Pension reform is a top priority for South Carolina’s treasurer-elect, who comes to office as the triple-A state’s pension funding level sinks further below the national average and as municipal investors and regulators are scrutinizing pension funds more closely.

Curtis Loftis, who will become South Carolina’s new treasurer on Jan. 12, said he’ll be wearing out his car on a statewide tour, speaking with Rotary clubs, church congregations, and chambers of commerce to build support for pension changes.

These changes may undo benefit increases South Carolina approved just two years ago. State lawmakers had hoped they could increase benefits for retirees by relying on higher returns from the stock market and other assets.

But under its current investment strategy, the pension fund is unlikely to achieve an 8% assumed rate of return on its investments, according to Loftis and an independent investment adviser.

Compounding the problem, the pension fund has seen its funding-to-liabilities ratio slip for the past several years. The South Carolina Retirement System fund, the state’s largest pension program with 457,332 members and $25.1 billion in assets, saw its funded level drop to 67.8% as of July 1, 2009, according to the latest available data from the state.

The level is down from 69% in 2008 and 86% in 2002, and it is below the 84% national average for state pension funds in 2008.

As the funding gap increases, bond investors will be watching for any potential impact on the state’s credit rating.

Should the 8% rate of return prove unrealistic, that may get South Carolina in trouble with regulators, according to state sources. If bondholders are not given the full pension picture, the Securities and Exchange Commission may pursue enforcement action.

For Loftis, the national attention surrounding pension deficits has focused South Carolinians on the problem, and now they are ready to act.

Pension reform “is almost job No. 1 for me,” said Loftis, who beat the incumbent treasurer, Converse Chellis, in the Republican primary and ran unopposed in the general election.

“The crisis around the country makes it easier for us to do things here,” he said. “I think that people will get together and I think we can craft a solution.”

Loftis acknowledged the 8% rate of return “is probably too high.” He added that the pension fund could consider a greater allocation to private equity and real estate investments to boost returns.

A private adviser’s report submitted to state officials in September said the pension fund’s current allocation strategy is likely to yield a 7.5% return rate.

The report, produced by Booz & Co., a New York-based consulting firm, and marked confidential, said if South Carolina achieves only a 7% rate of return, its unpaid liabilities could swell by $1.15 billion in five years, equivalent to 6% of the state’s 2010 fiscal budget.

The report underscores a disclosure problem similar to the fraud case New Jersey settled with the SEC, one former state official suggested.

If officials know a 7.5% return rate is most likely, then for South Carolina “to turn around and tell the bond community, presenting them a financial picture of the state based on an 8% assumption, to me is fraudulent,” said Chad Walldorf, a former deputy chief of staff to Republican Gov. Mark Sanford.

In 2008, when the state approved an increase to an 8% return rate from 7.25%, it created $2.5 billion of assumed earnings for the pension fund, Walldorf said. With the higher expected returns, the pension fund increased the cost-of-living allocation to retirees to 2% from 1%.

“It was a typical political move to try to have our lunch for free,” Walldorf said. The General Assembly voted to override Sanford’s veto of the rate hike. The state’s Budget and Control Board, which oversees the pension fund and includes the treasurer, approved the rate increase in June 2008.

South Carolina also approved an accounting change to smooth fluctuations in the pension plan’s assumed rate of return. The accounting change now averages returns over 10 years from five years previously.

Most state pension plans use a five-year smoothing period. South Carolina’s pension fund is the largest in the country to have a 10-year smoothing period, according to Loop Capital Markets.

The Booz report said the new smoothing period “overestimates [the] total plan assets relative to their market value.”

Walldorf said the 10-year period “completely overstates the health of the state’s retirement system.”

For now, South Carolina’s pension problems are nowhere near what some other states face but there is concern among investors about funding levels.

“If you’re hanging around 80%, that’s pretty good,” said Troy Willis, vice president and senior fund manager at OppenheimerFunds Inc. “Once you get down below 80%, it starts to be a credit negative.”

When a state falls into a range in the 50s and 60s, “you probably should be downgraded,” he said.

Willis said he has not bought any Illinois general obligation bonds recently, partly because of the state’s 51% pension funding level.

He said he has preferred California GO debt, though the Golden State is rated below Illinois, partly based on the pension issue.

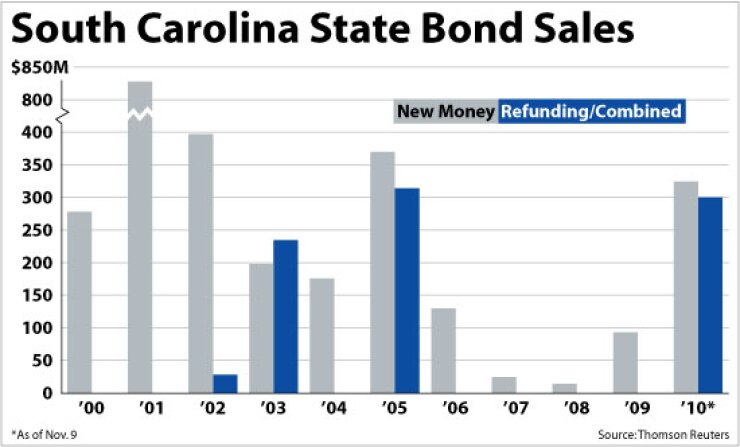

South Carolina last sold GO bonds in March, competitively issuing $170 million to Bank of America Merrill Lynch at a true interest cost of 3.27%.

Richard Marino, the lead analyst on South Carolina for Standard & Poor’s, said any decline in the state’s investment returns will be something to “talk to them about” and to analyze “what steps need to be taken to correct it.”

South Carolina is rated Aaa by Moody’s Investors Service, AA-plus by Standard & Poor’s and AAA by Fitch Ratings.

Loftis, meanwhile, said he is excited to hit the road.

To overcome the underfunding problem, he said his pension road show will address “all three legs of the stool” retiree benefits, participant contributions and the investment strategy.

He acknowledged that a discussion about reducing benefits or increasing contribution amounts will not be easy, while adding that pension-plan participants need to “understand their responsibilities and privileges.”

“We can’t just be afraid of talking about contributing what is due to the system,” Loftis said. “I’ve talked to state retirees and state employees and they understand there has to be a proper amount of money paid [into the pension fund]. I don’t believe there is a taboo to discuss that and I think we’re going to discuss that a lot over the next year.”

And by the time Loftis leaves office, he said he wants South Carolina’s pension program to be “considered the best in the country.”