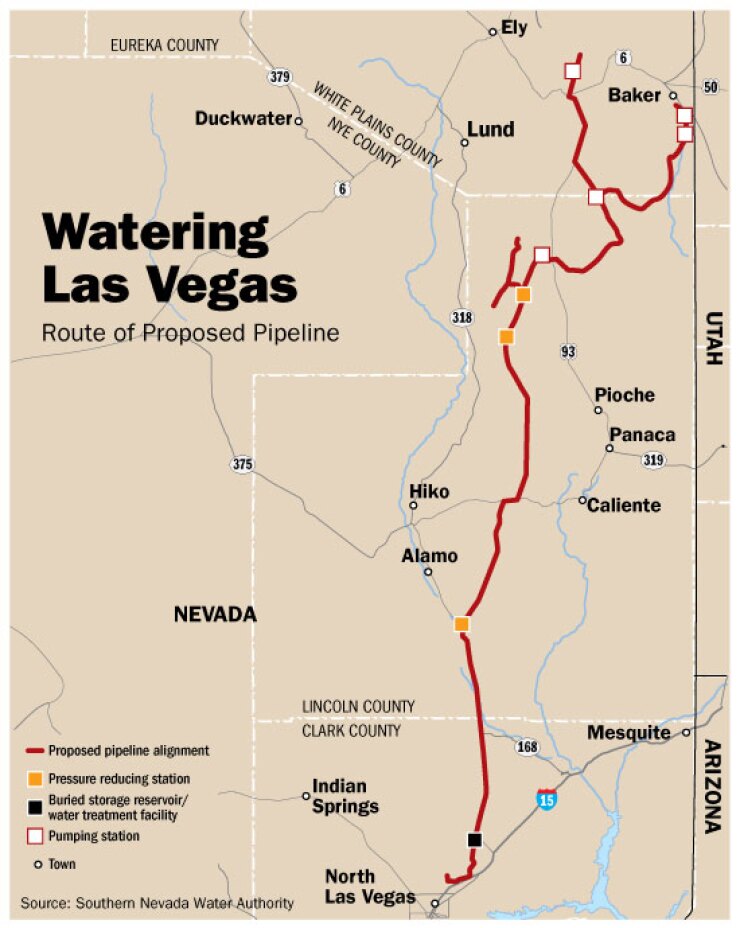

SAN FRANCISCO — A Nevada Supreme Court opinion earlier this year has thrown a big question mark into the Southern Nevada Water Authority’s plans to build 306 miles of pipeline to pump groundwater out the state’s rural northeast into metropolitan Las Vegas.

The authority is charged with securing water supplies for the Las Vegas metro area on behalf of its seven smaller water agencies.

The SNWA pitched the $3 billion pipeline plan as a backup source of water supply for the arid metropolis, which is almost entirely dependant on water from the Colorado River basin and its Lake Mead reservoir, which has dropped significantly over a decade of drought.

“Lake Mead is dancing precipitously close to when a shortage level would be declared,” said SNWA spokesman Scott Huntley. “It has been slowly been dropping closer and closer.”

Plans to ship groundwater out of White Pine County, Lincoln County, and the rural northern reaches of Clark County have aroused intense opposition there.

“The pipeline is pretty much viewed as an existential threat to rural Nevada, and adjacent rural Utah as well,” said Simeon Herskovits, a New Mexico attorney who represents the lead plaintiff in the state Supreme Court case, the Great Basin Water Network.

The nonprofit organization went to court to challenge the procedures the Southern Nevada Water Authority used to secure its water rights.

Back in 1989, the Las Vegas Valley Water Authority filed dozens of applications for groundwater rights in the three-county area. The SNWA became “successor in interest” for those applications after its 1991 formation, with the LVVWA as one of its members.

Nothing happened for years, until hearings were scheduled on many of the applications in 2006.

The Great Basin Water Network and its allies went to court arguing that the 1989 applications were subject to the state law at the time — since changed — that required Nevada’s water-rights arbiter, the state engineer, to act within a year. After a district court defeat, the Nevada Supreme Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs.

It’s a significant ruling, Herskovits said, because the state engineer’s office had excluded from its 2006 hearing process anyone who hadn’t filed a protest back in 1989 — thereby excluding a significant portion of the affected communities.

Those left out include anyone who bought or inherited land or water rights in the intervening years, as well as nonprofit organizations such as the Great Basin Water Network, which had not been formed back then.

The high court remanded the case to district court with instructions to determine a proper remedy, which could range from requiring entirely new applications for the water rights or simply a re-noticing of the hearings and a reopening of the protest period.

“A substantial number of people and citizens groups who were shut out of the process will be able to get involved,” Herskovits said. “They will have to use a properly open process.”

Both the SNWA and the state engineer’s office have filed petitions for reconsideration with the Supreme Court.

Its opinion has ramifications far beyond the counties affected by the agency’s groundwater applications, said Huntley, the SNWA’s spokesman.

“It has the potential effect of negating decades of water-rights rulings,” he said.

Herskovits disagrees — he believes Chief Justice James Hardesty’s opinion for a unanimous court is already narrowly tailored to address the SNWA’s applications in the three counties.

But Herskovits said that, in connection with the reconsideration petition, his organization may consider supporting a joint motion with its adversaries asking the high court to clarify that point.

It’s unclear what impact the Supreme Court decision will have on development of the groundwater pipeline, because, “there really isn’t a hard timeline,” according to Huntley.

“The construction aspect of this was still some time off,” he said. “And it was going to be based on whether or not there are serious water shortages from the Colorado [River].”

Aside from water-rights issues, the environmental permitting process is not complete, the spokesman added.

To cover its bases, the SNWA re-filed its applications after the Supreme Court ruling was handed down.

The estimated cost for the full build-out of the groundwater pipeline plan is about $3 billion, Huntley said. But any groundwater pipeline plan would be built in phases, he noted, starting with the sources closest to metro Las Vegas.

The drought, and its impact on Lake Mead’s water level, has already affected the authority’s considerable capital plan.

The current centerpiece of that plan is a third Lake Mead intake — built at a lower level, to prepare for the possibility that the lake may drop so much that the first intake becomes unusable.

“That is also designed as a reaction, if you will, to a lowering of the levels in Lake Mead since 2000, the beginning of the drought,” Huntley said.

The water agency has historically financed most of its capital programs with tax-exempt debt and, since the 2009 federal stimulus legislation, Build America Bonds.

The authority had more than $2.2 billion in municipal bonds outstanding as of June 30, 2009, according to its most recent annual financial report. The debt has been issued through a variety of agencies, including the Nevada State Bond Bank, the Clark County Bond Bank, and the Las Vegas Valley Water District.