The credit crunch that for weeks has roiled the municipal auction-rate market is now spreading to the market for variable-rate demand bonds, where issuers have sought cover from rising rates.

Much like the dislocation in the auction-rate market, the problems in the variable-rate market can be attributed to questions about ratings of the bond insurers and the constricted availability of Wall Street's capital.

In the last month, the ratings for XL Capital Assurance Inc. and Financial Guaranty Insurance Co. have been knocked down to the A-level from triple-A by the rating agencies, and other bond insurers are being reviewed for downgrades. This has made many money market funds - required to hold at least double-A rated credits under rule 2a-7 - nervous, and led many to shy away from the market or get out of certain floaters.

"The problem that we are having is that under rule 2a-7, as the bond insurers get downgraded, a lot of these bonds are no longer money-market eligible," said Paul Rosenstiel, the deputy treasurer of California.

And so money market funds have shifted the debt to the remarketing agents, like the 2007 top-three of Citi, JPMorgan, and Banc of America Securities LLC, which set the weekly reset rates for variable-rate debt. Faced with the potential of greater supply, the banks can buy up the bonds and take them onto their inventory, or they can direct investors to draw on the liquidity facility.

The banks "wanted to remarket them and the only way you remarket them is taking them in," said one Wall Street trader. "But with the suspect insurance, people put bonds back to the remarketers and they've reached their critical mass."

In increasing numbers, remarketers are directing investors to draw on the liquidity bank that backstops the variable-rate debt. Liquidity is called through a process of investors filing a tender notice to the trustee of their intent to put back the bonds. In some cases, remarketers are directing investors to do that even before attempting to sell the bonds.

"We're getting tenders on almost every bond we have out there every week," said Brian Mayhew, the chief financial officer for the Bay Area Toll Authority. "We haven't had an actual put to a facility yet."

It is this "put" that makes variable-rate demand obligations different than auction-rate securities. Liquidity provided by a letter of credit bank, or a standby purchase agreement provider, gives investors a guaranteed market for the securities if they want to sell them.

Most liquidity banks expect the facility never to be drawn upon, despite a 1982 regulation that said notices should be tendered every week to the trustee and then the bonds sold, Mayhew said. Over the last few decades, remarketing banks bought up any excess supply to support the remarketing,

"What was ordinary and customary would have deemed [hitting the liquidity facility] completely unacceptable," said Michael Marz, vice chair at First Southwest. "In the market we are in now what's ordinary and customary doesn't exist anymore. We are just trying to survive with overwhelming bad news every day."

Problems began to appear in the variable-rate market in November, when two New York colleges saw rates skyrocket on VRDBs insured by Radian Asset Assurance Inc.

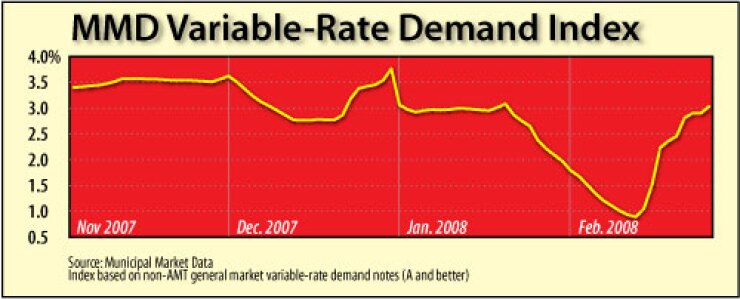

On Wednesday, the Municipal Market Data Variable-Rate Demand Index reset at 3.03%. That is a two-week jump of 214 basis points from the 0.89% rate it was at Feb. 13.

Rising rates and increased capital draws on liquidity providers could pose additional problems for issuers, especially for those looking to get out of auction-rate securities and into variable rate demand bonds. As liquidity banks find themselves facing increasing numbers of puts, they are also trying to deal with an increase in requests for liquidity and letters of credit.

"With the number of auction rates that tried to jump to VRDBs, I think everybody is at capacity," Mayhew said. "There is more capacity, but at a price that you would not want to pay and in terms that are probably unacceptable."

And that capacity seems to be for only the highest-rated credits. The state of Wisconsin, rated AA-minus by both Standard & Poor's and Fitch Ratings, and Aa3 by Moody's Investors Service, has had trouble finding liquidity for a commercial paper program, said Frank Hoadley, Wisconsin capital finance director.

"We've had one party say no and had some unenthusiastic responses from others," Hoadley said.

The state has steered clear of the variable-rate market because of concerns about many of the current issues, but Hoadley said several banks have said they had capital capacity concerns, while others said there would be time constraints in getting the deal done.

And in some cases, banks that have offered liquidity facilities for issuers looking to get out of auction-rate securities and into variable-rate demand obligations are now telling their clients they have to wait.